- Date

- vendredi 27 janvier 2023

As we head into the latter part of the winter, we may start to see danger ratings dropping in parts of the interior. But before we start making big plans, we should take a moment to reflect on the current state of the snowpack and the mindset needed for a safe second half of the season.

Deep persistent slab avalanches continue to be our biggest concern throughout the interior. These two avalanches failed naturally in the Purcells, near Golden on Tuesday, January 24. They failed on a layer of facets near the base of the snowpack. MIN photo from A SHERRIFF

State of the Snowpack

A deep persistent weakness exists throughout much of the interior. It has been popping up in different areas at different times and has been unpredictable, which makes forecasting for it difficult. Most recently, we have seen very large avalanches failing near the ground in the mountains around Valemount and Golden. Earlier in the month, we saw the same type of avalanches around Revelstoke and Nelson. We expect the weakness is still lingering through most of the interior and could produce very large and destructive avalanches with the right trigger. The layer seems most problematic at upper treeline and lower alpine elevations. We’ve also seen many reports of remote triggering of this layer, which means you might be able to trigger the layer from below the slope, from a ridge above the slope, or from an adjacent slope. This means you should be giving large, suspect slopes a wider margin of error than normal and be constantly vigilant about what is above you.

A layer of surface hoar from early January also continues to produce large and unpredictable avalanches. This layer is typically down 40-90 cm through most of the interior, making it prime to be triggered by the weight of a rider. This layer has been most reactive around treeline and the upper parts of below treeline elevations.

For a refresher on the deep persistent problem, check out the blog from our Senior Forecaster Mike Conlan from early January called “The Persisting Problem”.

A layer of surface hoar from early January remains reactive and resulted in this persistent slab avalanche in Rogers Pass on Wednesday, January 25. This layer continues to produce large, human-triggered avalanches throughout the interior. MIN Photo from SONDRE100.

Mindset

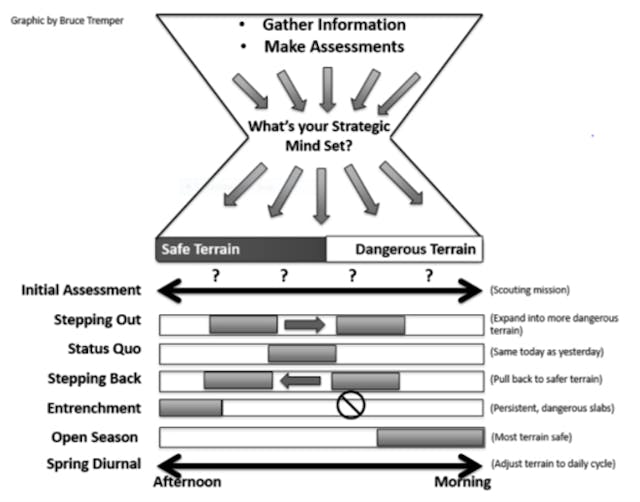

Strategic mindset is a term that is now well established amongst avalanche professionals in Canada. The original concept was established by Roger Atkins in a 2014 paper called “Yin, Yang, and You”. It establishes the following seven strategic mindsets: initial assessment, stepping out, status quo, stepping back, entrenchment, open season, and spring diurnal.

Two of the most common mindsets being used by professionals at the moment are stepping back and entrenchment. While we often associate the term entrenchment with the patience needed during big storms, the term has been used lately when referring to the approach to our deep persistent slab problem. Many professionals stepped back a few weeks ago when the large avalanches began to occur and have been entrenched since then. This means they are skiing the same runs over and over and avoiding pushing out into terrain that has not been used this season. They are sticking to low angle slopes and tight trees where they are certain the problem doesn’t exist.

The original strategic mindset diagram. The common thing with stepping back and entrenchment is that they both lead professionals to stick to safe terrain. Image source: Yin, Yang, and You, Roger Atkins, ISSW 2014.

In our forecasts, we often use the terms like ‘conservative’ or ‘patient’ mindset. We use these to mean people should to stick to simple, safe terrain and not be lured into bigger terrain features by boredom or ambition. It takes a lot of discipline to spend the whole season with simple objectives, but this is the attitude that professionals are using at the moment. It is the only way to ensure you don’t push yourself too far and end up triggering a large, unexpected avalanche.

The snowpack is highly variable throughout the interior, which makes it unpredictable. Unless something drastic changes in the snowpack, this could continue for the rest of the season in parts of the interior. One of our main concerns about this situation is that we can’t say exactly where and exactly when the deep layers will be reactive. This uncertainty is why we are continuing to issue warnings about the snowpack for most of the interior in our forecasts and communications.

First consider your mindset when planning your trip. Reassess your mindset during the day and ensure your travel habits are aligned with your mindset. Finally, assess if your mindset was appropriate while you are reflecting on your day.

Moderate vs. Considerable Hazard

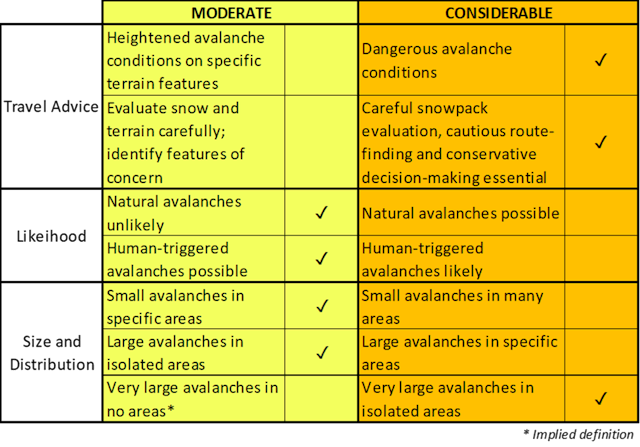

Over time, we may start to see the danger ratings drop to moderate for some of the interior. However, it is important to remember that this does not mean there is no danger. The persistent and deep persistent slab problems are expected to continue to be a major concern, even if we start to see the frequency of large avalanche events decreasing.

Forecasting for a deep persistent problem is complex, because it doesn’t fit nicely into the definition of either moderate or considerable danger. For example, the likelihood of triggering an avalanche might fit best into the moderate definition as the time passes, however the size and unpredictability of that avalanche fits more comfortably into the considerable definition. As forecasters and recreationists, we have to decide how much weight each part of the definition carries. Personally, I weight the travel advice section much higher than the likelihood section. I would also weight very large avalanches in isolated areas much higher than small avalanches in specific areas. With that in mind, I almost always lean more towards considerable than moderate in a situation like the example shown below. This is the classic low probability/high consequence problem associated with a deep persistent slab problem.

A hypothetical breakdown of Moderate and Considerable danger rating for the current deep persistent slab problem. How much weight would you put on each part of the definitions?

For more details on moderate hazard, check out this great blog post Managing Moderate from our Senior Forecaster, Grant Helgeson, who provides the following advice:

- Spooky moderate means slopes should be presumed guilty until proven innocent.

- Consider choosing terrain where the consequences of your snowpack assessment being wrong will promote a survivable outcome.

- An extra margin of error is needed if we are experiencing changes in temperature.

Few Instability Clues Don’t Mean Stability

One of the hardest things with a deep persistent slab problem is a lack of clues. When we provide advice on managing storm-related problems near the surface of the snowpack, we often advise people to watch for signs of instability like whumpfing and cracking, signs of wind loading, and observations of recent avalanche activity. These are all strong signs that the snowpack is unstable.

With a deep persistent problem, there are typically no obvious clues until it’s too late. The first sign of instability could be a large and destructive avalanche. This makes it very difficult to assess the problem in your local riding area. Bear in mind as you travel that a lack of clues does not mean a deep instability is not present in the area.

With a deep persistent slab problem, the first sign of an instability could be a large and destructive avalanche. Because the layer is so deep, there may be no clues that an instability exists until it is too late. MIN photo from MLDUQ

Clear Skies and Fresh Tracks

One of our biggest concerns for the coming weeks is that clear weather may motivate people to push into terrain that was previously unappealing in poor weather. The temptation might be strong, but we are cautioning people against pushing into untracked or unfamiliar terrain. Big, untracked slopes are one of the most likely places we would expect a deep persistent slab avalanche to occur. One of the most common themes amongst professionals when they talk about managing the current snowpack is the use of familiar terrain. They are sticking to previously skied terrain which they know is well tracked and tested. This approach can also be applied by recreationsists by selecting busy areas that get tracked out everytime it snows.

Large, untracked slopes may be alluring during periods of clear weather, but resist the temptation to push into bigger terrain, especially where a thin alpine snowpack may make it easier to trigger a deep instability. Photo: Ryan Buhler

Wrapping it up

Since we will likely be dealing with the deep persistent slab problem for the rest of the season in parts of the interior, here are some tips for managing terrain and keeping a disciplined mindset:

- Stick to simple, low angle terrain. Resist the temptation to push into bigger and steeper terrain.

- Remember that large, destructive avalanches can still occur with a moderate danger rating.

- Choose terrain that promotes a survivable outcome if an avalanche occurs. Consider: if the slope produces an avalanche while you are on it, what would the worst case result be?

- Use a conservative mindset even if you are not seeing clues of instability. Clues of a deep instability may not exist until it is too late.

- Plan to maintain a conservative mindset, even after evidence seems to indicate these instabilities are no longer a concern.

- Be willing to postpone plans for big, committed objectives and accept that they may need to wait for another year.

- The possibility of remote triggering means you should be leaving a wider margin of error around large, suspect slopes. An avalanche could be triggered from a location well away from the slope.

- Follow disciplined group decision making, ensuring that each group member is engaged in terrain selection. Speak up if you’re uncomfortable or think there’s a better option. Every voice in the group matters.

For more information on managing a persistent slab problem, check out these great articles from Powder Cloud called “How To Manage the Persistent-Slab Avalanche Problem” and “Know Where Not To Go.”