- Date

- jeudi 5 janvier 2023

The snowpack is spooky for much of western Canada

This year’s snowpack is different from most previous years. Professionals with decades of experience suggest this weak of a snowpack is only seen once every ten to twenty years for much of western Canada. Some professionals are comparing this snowpack to 2003, which was one of the worst years on record for avalanche fatalities. This winter presents a very different set of problems than normal and we need to adjust our mindset to remain safe.

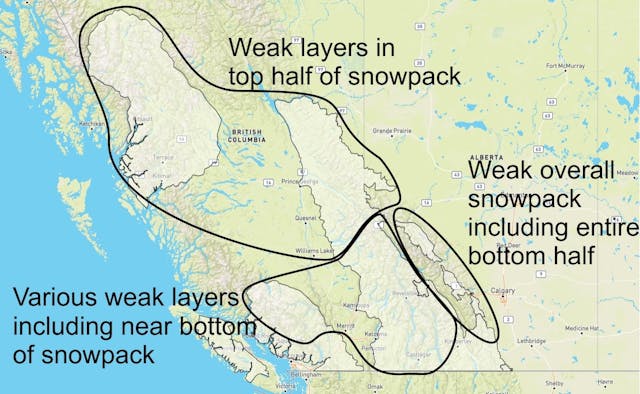

We experienced lengthy periods of drought and cold weather that created numerous problematic layers in the snowpack. The map below shows the status of these weak layers, with the caveat that there are small-scale variations which are better described in the daily avalanche bulletins. The setup of the snowpack varies across the provinces but there is a similar theme for most areas – riders have triggered large, scary avalanches with high consequences.

Avalanches can be triggered from a distance

One commonality we’ve seen is that many of the avalanches were triggered by riders from tens to hundreds of metres away from the slope that avalanched. This indicates that the buried weak layers are widespread and spatially connected, meaning you could trigger the layer anywhere on or near a slope. This is known as remote triggering and is a clear sign of an unstable snowpack. It also means that it is difficult to anticipate where avalanches may be triggered from.

The avalanche was remotely triggered from riders on the ridge above in the Selkirk Mountains (Eric Johnstone photo).

There may not be strong evidence that the weak layers exist

We often suggest looking for signs of snowpack instability to provide evidence that your riding area could be problematic. The complication with this snowpack setup is that the layers are deep enough that we are a lot less likely to see clues, like nearby avalanche activity, whumpfing, or cracking snow. If you do experience any of these then of course it is a strong sign to keep things tame, but right now we must remember that the first sign of trouble could be triggering a high-consequence avalanche.

Riders indicated they did not experience signs of instability before the avalanche in the Purcells (MIN user PURDY.LOGAN)

Many avalanches are triggered where the layers are shallowly buried

We may see a decline in the number of avalanches triggered by riders on these layers as they get deeper. Triggering is less likely when weak layers are buried deeper than about a metre because our stresses are absorbed by the upper snowpack. Where we are most likely to trigger deep layers is where they are shallow, or within that upper metre, which often can be found in wind-affected, rocky terrain.

A wide-propagating avalanche that released on a layer near the base of the snowpack in the Monashees (Vincent Jauvin photo)

Getting caught in an avalanche on this layer could be fatal

Given the widespread nature of these layers and their location deep in the snowpack, a triggered avalanche is likely to be large to very large (size 2 to 3 or more). We’ve seen several near misses of riders triggering large avalanches on these layers and narrowly escaping a fatal outcome. Professionals are treating the snowpack with an abundance of caution given the high consequence of being caught.

A rider escaped being caught in a large avalanche in the Monashees (MIN user MLDUQ)

A weak snowpack will stay around for a while

There’s uncertainty in how long these layers will persist, but it is likely that it could be a season-long problem in some areas. The weak layers have large grain sizes with poor bonding, and it can take months for them to shrink and start bonding as a cohesive snowpack. The season may not be long enough to experience this slow transition, meaning we could see large avalanches from these layers for months to come and even into early summer in the high alpine.

How to manage the risk

Professionals are stressing the absolute importance of “terrain, terrain, terrain” given the high consequence of triggering these layers. This is the year to be highly conscious about the terrain rather than the snowpack. Discipline and patience will be required to not step out when there is new snow or during a beautiful sunny day. A snowpack like this is unforgiving and cannot be micromanaged. Step back, think of the big picture, and ask yourself if you should be there in the first place.

Here are some further risk management strategies we recommend for areas with a persistent and deep persistent avalanche problem:

- Adopt a conservative mindset when in avalanche terrain.

- Be diligent about terrain choices, sticking to slope angles less than 30 degrees when in clearings, open trees, and alpine terrain.

- Follow disciplined group decision making, ensuring that each group member is engaged in terrain selection.

- Minimize exposure to overhead hazard, given that these avalanches can be remotely triggered and travel far in runout zones.

- Travel one at a time when exposed to avalanche terrain and regroup in safe spots well away from overhead hazard.

- Avoid exposure to terrain traps, such as gullies, cliffs, and trees to reduce the consequence of being caught in an avalanche.

- Practice patience, avoid complacency, and accept that you may need to manage this risk for weeks or months to come.

Remember that managing this risk doesn’t mean we can’t have fun. There are a lot of safe terrain features to play in, such as mellow slopes and dense trees. The avalanche forecasts are an essential part of planning for a safe trip. The nuances of the snowpack layers are described in the details tab of the daily avalanche forecasts and offer more information on safer terrain. Until we have clear evidence that this problem may be healing, we highly recommend a disciplined mindset focused on terrain selection.

Stay safe everyone.

- Mike Conlan