- Date

- Tuesday, December 20, 2022

I was just a kid when I first saw the iconic Stanley Kubrick movie, The Shining, but the final shot of Jack Nicholson frozen in the snow after being lost in the hedge maze stayed with me for years. Kubrick nailed it.

Years later, watching the movie as an adult who spends his days working in remote regions of the Yukon Territory, I can’t help but ask myself, “what could Jack have done to prevent his demise?”. “What are some steps he could have taken to better prepare himself for the environment?”

Every time we make the decision to head into avalanche terrain, it comes with the usual endeavors of planning and preparation. Or, at least it should. The Avalanche Canada Daily Process is something we should all adhere to as we undertake a day of backcountry travel.

However, when it comes to travelling in avalanche terrain when the weather is extremely cold, things get a little more complicated and we need to weight certain steps of our Daily Process more heavily. In particular steps 2 and 3.

PLAN YOUR TRIP

So, we’ve checked the avalanche forecast and verified through weather station data that it’s really cold out there. When we go through this process and see these conditions, we should immediately start thinking about consequences. It is a good practice to treat extremely cold temperatures much the same as we would a terrain trap when moving across a slope. The presence of a terrain trap means the consequences of being involved in an avalanche are much greater. The same goes for extremely cold weather. In an avalanche incident resulting in injuries, a race against time ensues. Even with the most ideal winter weather conditions, victims and rescuers often suffer from cold injuries, such as hypothermia and frostbite. In extremely cold conditions, these injuries can occur in minutes—making even minor incidents very difficult and dangerous when the temperature drops.

Extremely cold temperatures should be thought of much the same way as we think of terrain traps– they increase the consequences of being involved in an avalanche.

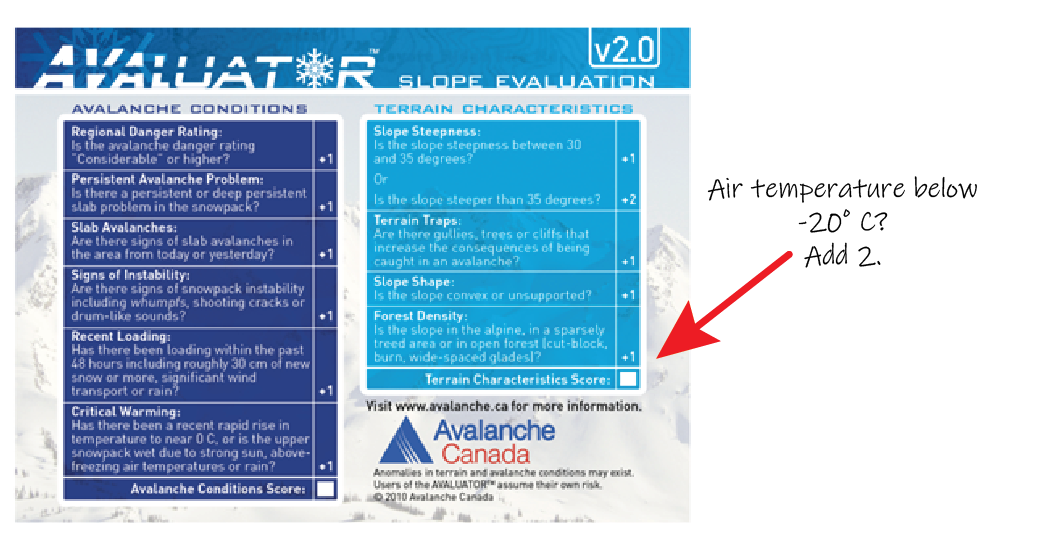

Another practice that can also be helpful when adjusting for extreme cold weather days is taking the avalanche danger rating and increasing the danger rating by one level, or adding a +2 to your terrain characteristics when using your Avaluator V2.0 accident prevention card. Either of these approaches help ensure you’re thinking with an appropriately conservative mindset when trying to decide where to ride when the weather is brutally cold. For example, when the avalanche danger is low and it’s very cold outside, we might choose to ride similar terrain to the choices we might make if the danger rating was moderate or even considerable.

Other adjustments we might make when venturing out on very cold days are:

- Plan objectives that are less remote and keep us closer to the trailhead or staging area

- Plan for shorter objectives and keeping our exposure time low

- Stick to simple terrain or non-avalanche terrain (if we are sledding)

- Ride in larger groups so that there are more people to help out if someone gets into trouble or suffers a cold injury. (Remember group size has its own risks and rewards though.)

- Slow down and build in an extra margin of safety for every decision, even those decisions that seem minor

- Avoid avalanche terrain all together

CHECK YOUR GEAR

So we’ve checked the avalanche forecast and weather and have decided to head out even though it’s going to be very cold. We’ve adjusted our mindset to include the potential consequences of the cold and we’re ready to start loading our backpacks and tunnel bags. It’s time to take a closer look at our equipment and the additional items we might include on a cold day. We also need to consider how we might manage certain pieces of equipment differently than we would on warmer days. Some of the things we might consider are:

- Ready-HeatTM Vests and Blankets. These are commercially available products that, once opened, heat up due to a chemical reaction. The vest can be worn under a jacket to keep a rescuer or an injured partner warm

- Outerwear rated for extreme cold. This includes larger down jackets and down pants, mittens instead of gloves, and face coverings

- Extra parts in our repair kits as things break much more easily in the cold, particularly plastic things

- Hockey stick tape to help skins stick when they fail in the cold…because they will. You can also consider putting your skins under your jacket during the descents. This will help them stick better in the cold

- Foot and hand warmers

- Fuel line antifreeze

- Extra fire starting materials

- Remember items with batteries can be less reliable in the cold. Make sure you bring an extra battery pack and cables to keep electronics charged. If you’re carrying these items close to you to keep them warm, don’t forget they should be 20 cm from your avalanche transceiver in transmit mode and 50 cm when you’re searching.

- Avoid the use of heated jackets and gloves as these can interfere with the performance of your avalanche transceiver

PLAN FOR A RESCUE

Finally, consider the implications of having to execute an effective companion rescue and potential patient extraction in extremely cold temperatures. This video from the Yukon Region discusses what those might be.

There are a number of potentially life-saving pieces of equipment we can add to our kit on extremely cold days. An expedition weight down jacket and pants might be at the top of the list.

Ultimately, extremely cold weather adds a layer of complexity to a day in the backcountry. It also increases the level of risk we expose ourselves to. The fact of the matter is, we live in Canada and every winter we experience prolonged periods of very cold weather so understanding the implications of the cold and knowing how to adjust our trip plan and equipment needs accordingly will help ensure a safer outing when the mercury drops way, way down.