- Date

- jeudi 7 février 2019

Making sense of the current avalanche danger at lower elevations

In mid-January, snow began to bury a robust layer of surface hoar that was widespread in the trees but largely absent from the alpine. This layer was very active when it was first buried. At that time, Avalanche Forecaster Ilya Storm commented that he saw some super goofy crowns in benign 20 degree terrain. On more normal riding terrain (30 degrees), the snow on top of the surface hoar was flowing like water and running super far.

This layer is prevalent throughout the Interior Mountains of British Columbia with the North Columbia being the clear hotspot. As we moved through the end of January it became less reactive, waiting for another load.

Fast forward to the first weekend of February. A storm started warm before transitioning to brutal cold. Just off the valley floor there wasn’t a breath of wind and riding conditions were phenomenal. But there was a catch; the surface hoar had roared back to life. Folks were triggering large avalanches in the trees between about 1400 and 2000 m throughout the Interior Mountains. Scenes like the photo below were the norm last weekend and it felt downright spooky.

This photo submitted to the Mountain Information Network by Jeff Harker. It’s a great MIN, check it out here.

This photo really got my wheels turning. This has been daily-driver terrain for a lot of folks this year. Weak layers have been pretty quick to heal. My entire season is a blur of epic tree riding across the province. But it’s changed. The trees are now the spookiest place to be throughout the Interior Mountains.

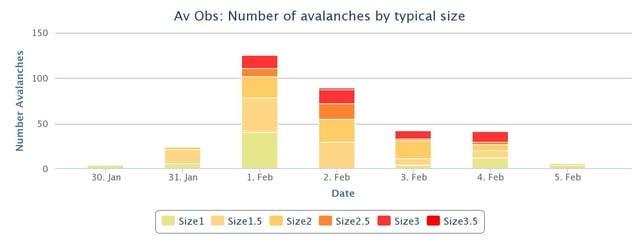

This graph does a good job of summarizing the recent avalanche cycle in the North Columbias:

It went off over the weekend and now it’s quieting down. So we’ve got pretty cold weather, and the hazard rating for many regions is right on the border between Moderate and Considerable. Why issue a SPAW? It really comes down to the fact that this is an atypical situation. It’s most dangerous in the trees right now, and we expect that trend to continue right into the weekend.

A weak layer at and below treeline brings its own set of hazards. At lower elevations there are more terrain traps that can multiply the effects of being buried. Even a small avalanche can drag you through trees, push you over a cliff or stuff you into a gully. At these elevation bands avalanche slopes are smaller and more subtle, making them more difficult to identify. And we all need to adjust our mindset; the trees are more hazardous than the alpine right now, which is pretty much the opposite of what we are used to.

The cold weather has “tightened up” the snowpack a bit, which has contributed to the reduction in avalanche activity. But it’s not cold enough to affect that persistent weak layer (PWL) that’s buried anywhere from 50 to 100 cm deep. It’s also worth noting that cold weather compounds mistakes in the mountains. Even small avalanches can have significant consequences at these temperatures, when we can so quickly become hypothermic.

Moderate vs Considerable

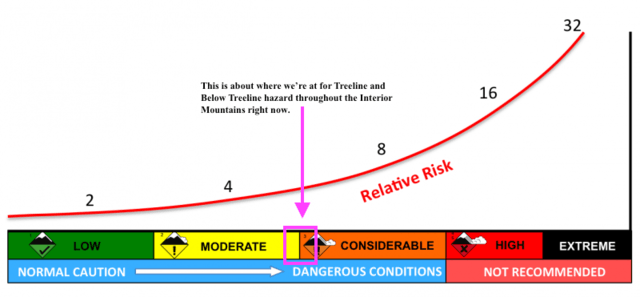

Depending on your location, the danger rating at treeline and below treeline is either moderate or considerable. We’ve spent a lot of time in our office discussing the current hazard over the last few days and when we look at the danger scale as a continuum, we’re probably somewhere between 2.8 and 3.2. Something like this:

The line marked “Relative Risk” demonstrates how the danger scale is not a linear progression.

The Utah Avalanche Center put out a great piece on the avalanche danger scale, which explains this point clearly. Check it out here https://utahavalanchecenter.org/avalanche-danger-scale.

Finally, I want to touch on the idea of “feel.” With wind slab avalanches you can feel the slab underneath your skis or machine. It stiffens up and offers feedback, which makes them relatively easy to identify and deal with. This PWL is now 50 to 100 cm beneath the surface and frankly, it feels fantastic underneath your skis or machine. As the surface continues to facet with this cold weather, the feel will only get better. But the problem within the snowpack isn’t going to go away anytime soon. We’re expecting quite a bit of wind this weekend which may degrade the riding quality in the alpine. This could drive folks down into the trees where the potential for an accident is highest.

We’re very confident the conditions driving this SPAW apply to the Cariboos, North Columbias, South Columbias and Purcells. The South Rockies, Lizard Range and Kootenay Boundary are right on the tipping point. In these regions the PWL is in place, the problematic snowpack structure is in place, but there’s less load and the overlying slab property isn’t quite the same. This means the conditions aren’t quite as reactive when compared to the other regions.

So, what’s the recommendation going forward into the weekend? Recognizing and avoiding avalanche terrain at and below treeline. If the visibility holds up high, you probably want to get to the alpine, but you need to tip-toe through the trees. I would avoid cutblocks, gullies, creek bottoms, convexities, steep openings and any other terrain traps in the trees like the plague.

Even playing on the cutbank above a road could bring the slope down on top of you. If there’s a ditch, that’s a perfect terrain trap. If you’re riding a sled, stick to the groomed trail and don’t play on your way to the alpine. If you’re skiing, accessing the alpine via the lifts is a good way to skip traveling in the trees. If you’re skinning from highway elevations, choose very well supported, gently inclined and heavily treed slopes for your access and egress to the alpine. If this sounds overly complicated, or beyond your scope, think about hiring a certified guide.

And remember, even in the alpine where danger ratings are lower, wind slab avalanches are still a potential problem as described by this great MIN submission we received on Wednesday. Increasing wind speed this weekend will likely exacerbate this problem.

Have a safe weekend, and please let us know what you’re seeing out there by submitting to the Mountain Information Network.

Written by: Grant Helgeson